Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches.

This week, we cover Erin Brown’s “A Brief and Hideous Scrawl,” first published in the Spring 2022 issue of Fiyah. Spoilers ahead!

“There were so many sweet memories of being curled up around a writhing new meal in the back-alley behind the opera house, a juice unfortunate beating against his jaw with their tasty toothsome fists. And the sounds, the sounds, the peak and crescendo of their last terrible cries—well, it moved him.”

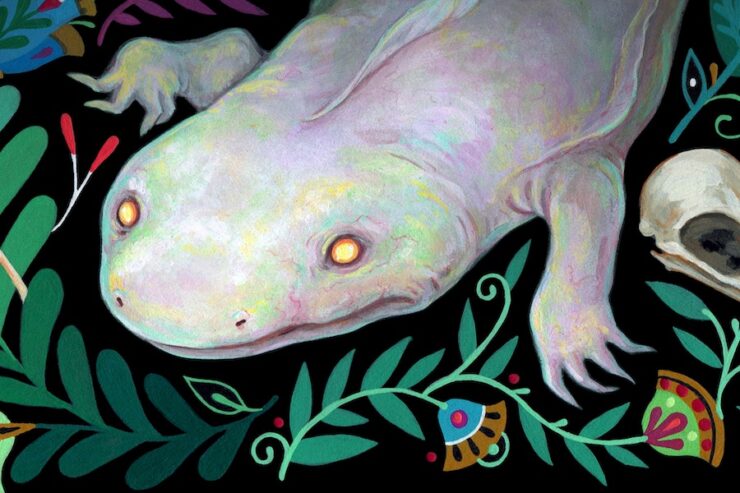

A human named Berecht will describe the beastling as a head taller than a man and only a little broader. Like “a lizard, a lizard made of moldy slimy ashes, like a stretched-out toad with teeth.” The beastling will disdain this portrait, for his black scales gleam so brilliantly that he needs deep shadow or a coat of mud to conceal himself from prey.

For a long time he’s lived in the city, in an alley behind an opera house. At first he found the city beautiful, its truffle-and-wine flavored inhabitants luscious. They writhed and screamed so gratifyingly. Yet how could one artfully defile a place where one’s “bloodiest efforts were lost and trivial, sucked into the whirlpool of frequent evils”? Men would come in siren-blaring vehicles to scoop the shredded remains into black bags and then speed off, leaving the beastling “undetected, uncelebrated.” At last this meaninglessness existence has driven him to stow away on a freight train heading anywhere else.

A diet of train-hopping vagrants, tasting of “caustic rot,” sickens him, but at the end of the tracks he finds himself in a forest smelling of “herbally clean air” and resounding with birdsong. A chance meal of human-child confirms his positive impression. At nightfall he explores. Mere beastling-bounds beyond the forest is a mud-brick walled village of small houses and a central square with a bubbling fountain. It reminds him of opera house sets, the sort of storybook town where people believe what they see and wield pitchforks accordingly. He retreats to the forest, for now.

One morning as he idly braids twigs into a circlet, a man approaches. The beastling scurries up a tree and watches the man discover the gory remnants of his child-meal. Instead of screaming out in fear, the man quietly says “hell” and walks away The beastling follows through interlacing branches. He accidentally drops his circlet next to the man, who freezes, pisses his pants, yet only says “hell” again before deliberately heading back to the village. It’s so strange that the beastling doesn’t pounce. That night he slips over the wall, tracks Piss-Pants to an alehouse and eavesdrops on his tale of finding Heimlin’s missing boy. From the ensuing conversation, the beastling gathers that these humans worship a forest-presence by hailing it (“hail,” not “hell”!) and appeasing it with sacrifices.

Back in the forest, the beastling ponders the possibility of being so “loved and feared, fed and endured, welcome and greeted.” It returns him to hopefulness. Whatever the danger, he’ll try to become the villagers’ god. As a first step, he slaughters a woman, leaves her body in the fountain-square, and spies on the villagers’ reaction. They turn to a man named Grosher, apparently an authority on “the Good One.” Is this his work, and if so, why didn’t he devour Hildy whole? Hard to know the Good One’s mind, Grosher says, but maybe he didn’t like the taste of the onions she habitually ate.

The villagers construct Hildy’s pyre at the forest edge, Grosher reasoning that if the Good One likes onions, he’ll eat her. If not, the burning could signify their contempt of onions! In fact, the beastling likes onion-infused meat. He considers adopting “the Good One” as his name. He has thought of himself as “a brief scrawl of hideous calligraphy writ on the world,” or “Scrawl” for short, but “the Good One [was] classic, as beast names went.”

He finishes off Hildy; belly full, he contemplates teaching the villagers that he craves suffering and fear from his prey, not mere submission. A fat man comes to tend Hildy’s pyre. The beastling attacks just to wound, to torment. The man stuns him with his shovel, stands gesturing for a minute, then stumbles village-ward.

From a rooftop the beastling watches the fat man, Berecht, berate himself to the villagers for having even thought of denying the Good One. To ask his mercy for one person will condemn ten people, as Grosher reminds everyone. Berecht’s defense is that his assailant actually wasn’t the Good One but a comparative nothing of a lizard-toad monster. Still, he’s committed a thought-crime and must present himself to the Good One.

The villagers crowd into a forest clearing, avoiding the dirt-circle at its center. The beastling watches from a tree as Berecht summons their god, the rest echoing “Hail.” With Grosher’s coaching, Berecht manages a sincere self-offering. Black whips like tentacles emerge from the earth and tear him to shreds. His screams should satisfy, but the beastling’s too horrified by the stone-faced silence of the villagers to enjoy them.

Then the tentacles attack the beastling. Their grip burns like acid, agonizing. He claws and bites, roaring, finally managing to wrest free and drag himself into the shelter of the trees, where he passes out.

He wakes half-flayed and missing a leg. Crows have tried to feast on his leg stump; poisoned, they lie dead around him. The beastling plucks and eats them to fuel his healing, at the same time weeping for the “untasted, unappreciated, unloved” villagers. He weeps, too, with longing for his opera house. He’s forgotten to love his city, but now the meal of crows brings him pure joy; even in his ravaged state he feels hope and stubborn strength.

His experiences have inspired him to write his own opera. It will be an epic tragedy, autobiographical, “glittering with the glamour of his perfectly novel viewpoint…with music both human and inhuman,” telling the story of the village and “the unthinkable evil beneath the earth.” He won’t even eat the actors, if they follow his instructions.

The beastling feeds while “composing scores in his head alongside the symphony of crickets.” Then he slides into healing sleep, “barely waking to the lonely moan of a distant passing train.”

What’s Cyclopean: Our protagonist monster has poetic inclinations, styling himself as “a brief scrawl of hideous calligraphy writ on the world, a blunt and blasphemous word.” He “liked the way it sounded,” though he doesn’t seem to have thought deeply about what greater power might write such a word.

The Degenerate Dutch: The Scrawl tends toward gentrified tastes, preferring people flavored with “avocado and truffles and wines and good coffee” over the vagrants “arguing in languages from heavens-knew-where” and swigging ditch-liquor.

Weirdbuilding: The scarier a monster is, the more amorphous tentacles it has. Obviously. Less scary monsters are merely batrachian.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

What makes a carnivore evil? Not just anthropophagy; some monsters don’t have a choice about eating people, or don’t know what they’re doing. The Scrawl, however, not only chooses to eat people (versus birds, which he can get by on just fine), but prefers the aesthetic when they suffer. When they struggle.

In contrast, the Good One prefers submission. And not only submission, but the pigeon-dance of sacrifice, of people guessing at its whims and offering themselves and their brethren up as appeasement. The Scrawl is a serial killer; the Good One is Big Brother. “I ran in my heart” is the language of thoughtcrime, of secret police and family informants. Of sacrificial pigeon-dancing in response to malignant whims. Of hopelessness. Anyone in the town could leave for the city, and avoid getting eaten by anthropophagous monsters by avoiding the opera house, but they don’t.

Of course, anyone in the city could also avoid getting eaten by anthropophagous monsters by avoiding the opera house, but they don’t. The opera house hasn’t been shut down, or hired a guard cadre of Slayers. If you’re a professional singer in the city, you probably have only so many options for places to work, and thus to eat. So that’s a different sort of evil. The Scrawl suggests that the city is a place of denial; the country is a place where people “believed what their eyes saw.” Which is true in this case, though not the way he expects.

Evil centers itself. The Scrawl’s first thought, when his attacks come as no surprise, is not that he’s been preceded but that he’s been foretold. And then, faced with competition, he immediately turns the confrontation into an opera about his tragedy, and the anguish of discovering yourself a smaller evil than you believed. Which makes him happy—I suppose there’s something to be said that he gets at least as much from his own suffering as that of others. But still, claiming the story of your own triviality as a story centering yourself is…

Well, it’s cosmic horror, isn’t it? Most of our stories about an uncaring universe in which all of human effort means nothing… center humans, and the psychological effect of coming to grips with that universe. So maybe this is a story about how we get art out of suffering, and whether art redeems that suffering or merely provides a convenient justification for maintaining it.

Or maybe it’s a story about how tiny monsters are horrible and unsympathetic until you watch them scrap with larger and more horrific monsters.

Or maybe it’s an AU crossover between City Mouse/Country Mouse and Phantom of the Opera. City monster falls into ennui and leaves for the glories of the countryside, where he discovers that country monster life is very different, and returns to the city with new insight about the value of his home? Mauled monster is inspired to create, and force the performance of, an opera based on his experiences? You could kind of adapt this story into a musical, if you were so inclined. It would certainly startle the critics.

Nobody expects the Anthropophagous Toad-Monster of the Opera. Or at least, I didn’t. But somehow I find it a welcome—if blood-drenched—surprise.

Anne’s Commentary

It’s been a while since we read Lovecraft’s “Nameless City” and Langan’s “Children of the Fang”—past time for another good lizard-monster story! Bonus points because it’s a true lizard-monster. Erin Brown’s beastling himself admits he’s no dragon, nor does he seem to belong to clade Dinosauria. I have a (tiresome?) habit of trying to relate fabulous creatures to real-world models. Take Voldemort’s snake-familiar Nagini, who seems to be a cross between a green anaconda and a viper with highly hemotoxic venom rather than a true cobra of genus Naga as her name might imply. I would have given Voldemort a queen of a king cobra (Ophiophagus hannah), but then I think all dark lords should sport king cobra capelets.

Why wouldn’t they? Unless, fine, their tastes run more toward black mamba belts or Gaboon viper collars.

I’m not claiming Brown’s beastling model must have been the one I quickly saw in Scrawl, or that she had to have a real-world model at all. Scrawl’s clearly a fabulous creature in his high intelligence and Lestat-level propensity for existential moping. There’s also his apparent ability to slip from one reality or dimension to another. I don’t know where the vagrants were going on that freight train, but it carries Scrawl straight into a “storybook world” worthy of the Brothers Grimm in afterlife collaboration with Lovecraft. What’s more, Scrawl recognizes the fictional tropes inherent in the walled village and enchanted forest. Has he gained all his knowledge of human culture from the opera house? The majority of it, perhaps, as he doesn’t wax nostalgic about libraries or comic book conventions or TV glimpsed through the windows of electronics stores.

Would you like to meet Scrawl at your next Comic Con? He’d demolish the cosplay contest. Maybe too literally, unless he protein-loaded beforehand.

Morphologically and behaviorally, Scrawl strongly resembles members of real-world genus Varanus, the monitor lizards. The most famous of these, and the largest, is the Komodo dragon. Scrawl might match this particular “dragon” for length (10 feet overall), but he seems more lightly built, about as “skinny” as a man, Berecht reports. Of course, Scrawl is probably not full-grown; the clue is that he’s a “beastling,” not a “beast,” hence subadult. This makes sense, given Scrawl’s rather adolescent swings between grandiosity and depression. Komodos can run fast, up to 12 miles an hour, which is plenty fast enough for them to catch humans, though unlike Scrawl, they certainly don’t specialize in people-eating. Their bite delivers a true venom along with the nasty bacteria it can also pass along. The venom inhibits blood clotting, causing prey to hemorrhage excessively. Scrawl’s victims do bleed a lot, but unlike the Komodo, he doesn’t patiently wait for blood loss to enfeeble or kill them, so maybe trauma alone explains their exsanguination.

Another model for Scrawl could be the crocodile monitor. It approaches the Komodo’s length because of its extremely long tail. It’s much more lightly built. Its teeth, being long and serrated, are notoriously damaging. Like Scrawl, they’re adept arborealists but may also hang out and sleep on the ground, and they can rear up on their hind legs to “monitor” their surroundings. Indigenous people speculated that this animal could be counted on to give a warning cry if actual crocodiles were around, that “monitor” thing again. I don’t think Scrawl would be so helpful.

A last, and scariest, model could be the extinct Australian varanid Megalania, at a length as much as 23 feet and weight possibly topping 2 tons. You would not want to meet a full-grown Megalania behind your local opera house.

Not that you’d want to meet Scrawl…

Curiously, the genus name Varanus is derived from the Arabic waral, meaning “lizard beast.” Which is just what Scrawl will be, when he grows out of “beastling” status. I say when, not if, what with him having the strength to escape the Good One. There’s an ironic name, though the villagers probably fear that any negative designation would anger this black-tentacled entity. Evidently it only takes sincerely willing sacrifices, but as Grosher admits, it’s hard to know the Good One’s mind. I’m afraid the GO might have so diabolically cold an intelligence that he (the villagers’ pronoun) takes pleasure in the additional agony that asking to be devoured must cause.

Scrawl isn’t as icy as all that. He’s horrified by the stony, dead faces of the villagers as they watch Berecht die. Is not such defensive detachment, such “ancient, weary terror,” monstrous? Is not part of the tragedy of Scrawl’s projected opera that Grosher is despite his seeming calmness a “broken man”?

Speaking of irony, Scrawl comes off as more emotionally alive and empathetic than the villagers. He even weeps for their “unending torment, torn but untasted, unappreciated, unloved.” Unlike the “unthinkable evil” which is the Good One, Scrawl would have appreciated his worshippers and given their deaths a “thinkable” meaning. And returning to his opera house, he will give the villagers meaning, through art.

Surely that will pay for his eating Heimlin’s boy and Hildy, a mere two individuals in exchange for collective immortality! Or such would likely be the reasoning of a brilliant, angsty, monitor-lizardy adolescent, wouldn’t it?

Next week, we continue N. K. Jemisin’s The City We Became with Chapter 15: “And lo, the Beast looked upon the face of Beauty”. Can it really be a meet-cute when Beauty is sleeping and might eat you when he wakes up?

Ruthanna Emrys’s A Half-Built Garden is now out! She is also the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. You can find some of her fiction, weird and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic, multi-species household outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.

It just occurred to me how often we’ve seen the EGO of these little god-wannabe creatures. Fritz Lieber’s Smoke Ghost, that horrifying skull ring in Tara Campbell’s Spencer, and this Scrawl are all self-centered in a way that makes them pathetic despite their power. That’s so interesting. You know how Terry Prachett had this idea that anything exists if people believe in it? I love this alternative, that these things exist and are desperate to be believed in.

Oh, also, Anne and Ruthanna? This review never ended up in the master list.

@Moderator Can you please add this to the master list?

@2, 3: Sorry about that–should be fixed now. Thanks, and happy new year!